IB Diploma students, Creativity, Activity, and Service (CAS) can sometimes feel like one more requirement in an already demanding programme. But what if one of the simplest daily habits, walking to and from school, could meaningfully fulfill all three strands of CAS?

Walking 30–45 minutes each day provides consistent, low-impact cardiovascular exercise. That alone should be reason enough, but we can sweeten the deal even more. Unlike intense gym sessions, walking is sustainable and accessible. Over time, it improves heart health, supports healthy weight management, and increases overall stamina. For students who spend long hours sitting in class or studying, this daily movement is especially important.

Beyond physical benefits, walking offers something equally valuable: quiet time. A phone-free walk creates space to think, decompress, and mentally reset before and after school. The DP Psychology students will tell you that research consistently shows that moderate aerobic activity reduces stress and anxiety, improves mood, and enhances concentration. For IB students managing deadlines, Internal Assessments, and exams, this mental clarity can make a real difference.

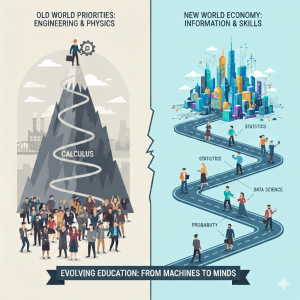

The ‘Activity’ strand of CAS is clearly addressed through daily walking, but the experience can go further. Students could systematically record data such as walking time, step count, body weight, resting heart rate, post-walk heart rate, and even blood pressure. Over several months, this dataset could form the basis of a Mathematics Internal Assessment, exploring correlations, regression models, or statistical trends related to fitness improvement and grades.

Creativity might come in the form of designing a poster campaign promoting active commuting. Students could create infographics showing health benefits or data from their own tracking project. This not only fulfills the ‘Creativity’ component but also strengthens communication and design skills.

Finally, Service could involve encouraging other students, or even teachers, to join a ‘Walk to School’ initiative. Organising a weekly group walk, tracking collective distance, or raising awareness about physical and mental health connects personal growth with community impact.

Walking to school may seem ordinary, but within the IB framework, it becomes a powerful, multidimensional CAS experience, benefiting the body, strengthening the mind, and contributing to the school community.